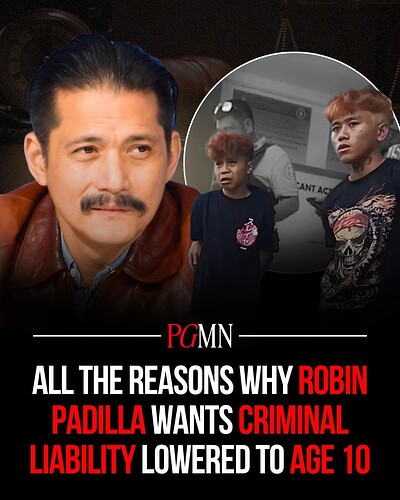

Senator Robin Padilla is pushing for amendments to the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act of 2006, aiming to lower the minimum age of criminal responsibility to 10 years old—but only in cases involving heinous crimes.

For Padilla, this is not just about legislation—it’s about protecting victims, fixing legal blind spots, and responding to the harsh realities on the ground.

One of the clearest examples fueling Padilla’s call is the recent killing of a college student in Tagum City. The 19-year-old victim was stabbed 38 times inside her home.

Authorities arrested four suspects—two of them minors, aged 14 and 17. Despite the brutality of the attack, the 14-year-old will not face criminal charges under the current law, which exempts children under 15 from liability.

Instead, they are placed in intervention or diversion programs regardless of the severity of the crime.

What the Current Law Says

Republic Act No. 9344, or the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act of 2006, defines how the Philippine justice system handles minors in conflict with the law. Under this law:

• Children below 15 years old are exempt from criminal liability, even if they commit a heinous crime. They are instead placed under intervention programs—counseling, education, and community service—with parental or guardian involvement.

• Children aged 15 to below 18 are also exempt, unless they are proven to have acted with discernment—meaning they understood that what they were doing was wrong. Even then, they are often given suspended sentences and rehabilitative options instead of jail time.

• The law focuses on restorative justice, which means helping children reform instead of punishing them.

Padilla believes this approach, while well-intentioned, is being abused.

He has raised concerns that criminals are taking advantage of the system by recruiting minors to commit serious crimes, knowing they will face minimal consequences under current laws.

Padilla pointed out that children today are exposed to technology at a much younger age, which he believes contributes to earlier moral discernment.

For him, this means young offenders are more capable of understanding the consequences of their actions—and should therefore be held accountable for heinous crimes.

He emphasized that the measure is not about punishing children but about providing structured accountability.

Padilla clarified that his bill preserves key protections already in place: automatic suspension of sentences, intensive rehabilitation, and community-based intervention programs.

What it adds, he says, is a serious consequence for the most serious crimes—without taking away a child’s chance at reform.

“Bilang ama at lingkod-bayan, naniniwala akong dapat may pangalawang pagkakataon ang kabataan pero dapat din ay may malinaw na gabay at pananagutan. Hindi ito simpleng parusa. Gusto nating palakasin ang rehabilitasyon at intervention programs para matulungan silang magbago at makabalik sa tamang landas,” Padilla said.

What Padilla’s Proposal Would Change

Under Padilla’s proposal:

• Children aged 10 to 17 who commit heinous crimes—such as murder, rape, drug trafficking, and robbery with homicide—would be eligible for criminal liability.

• Children under 15 who commit non-heinous offenses would still be placed under intervention and diversion programs supervised by their parents or guardians.

• Repeat offenders aged 15 to 18 would be required to undergo intensive rehabilitation.

• The automatic suspension of sentences for minors would remain in place to ensure rehabilitation remains a priority.

Padilla maintains that reforms are urgently needed to close legal loopholes, adapt to the realities of modern youth behavior, and ensure that those responsible for grave crimes are no longer shielded by outdated protections.

Daming bangag na ngayon sa Admin